Differences Between Law School in Venezuela and the U.S.

As a foreign lawyer, I’m often asked about the educational system in Venezuela and how it differs from the one in the U.S. The biggest difference is that in Venezuela, law school is an undergraduate program, meaning it’s something you pursue right after high school. The program lasts at least five years, and after graduating, you receive your law degree. To practice, you need to register with the national Bar Association and get a membership number known as “Inpreabogado.”

In the U.S., becoming a lawyer requires a postgraduate degree—a doctorate, to be specific. This means that in America, you must not only have your high school diploma but also a bachelor’s degree before you can even apply to law school. You also need a high score on the LSAT, the law school admission test, to have your application considered. Getting into law school in the U.S. is highly competitive, with your profile, credentials, and experience being compared to other applicants to determine who is most qualified to earn a JD degree.

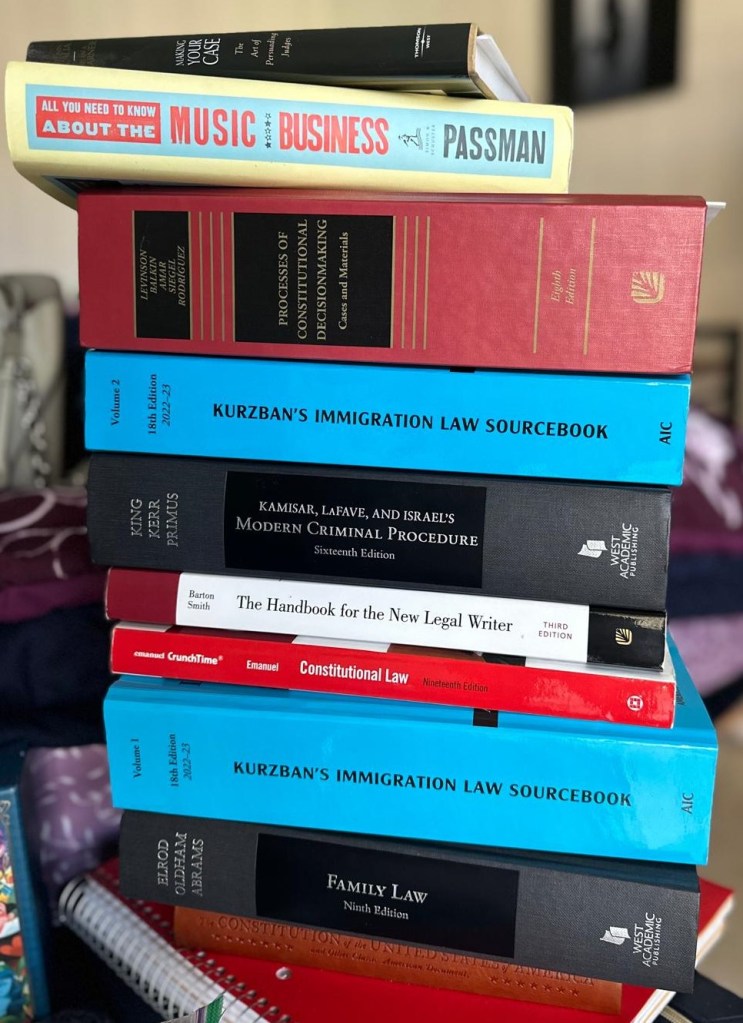

There’s another postgraduate program called the LL.M. (Master of Laws), which lasts at least a year. You must have already completed your JD to start the LL.M. program. Even though our law degrees don’t allow us to practice in other countries (especially not in the U.S. due to its completely different legal system, “common law”), many universities offer special LL.M. programs for foreign lawyers, allowing them to use their home country’s law degree for this master’s program. Some universities also offer a combined LL.M./JD program for foreign lawyers.

So how does it work? During the first semester of the LL.M. program, a foreign lawyer can apply to transfer to the JD program without taking the LSAT. If accepted, the foreign lawyer will receive both degrees at the end of the combined program: the U.S. law degree (JD) and a master’s in law (LL.M./JD).

Given all this, you can see that the level of rigor in U.S. law school is higher since it’s a postgraduate program. The Juris Doctor (JD) program lasts three years, and each year is known as 1L, 2L, and 3L. Even for Americans, law school is a big challenge, and the first year (1L) is particularly tough—it’s a major hurdle that’s hard to overcome. It’s like entering a completely different world with new vocabulary, new ways of thinking, speaking, writing, reading, and viewing the world.

What Is the Socratic Method?

Another major difference is the teaching method. In Venezuela, especially in undergraduate programs like law, it’s common for professors to lecture, breaking down each topic, explaining every detail, and allowing students to ask questions whenever they have doubts. But that’s not how it works in U.S. law schools.

In the U.S., law schools use the Socratic method of teaching, where students are called on directly by name to answer questions about legal cases, doctrines, and concepts.

The Socratic method is a form of logical inquiry and debate used to explore new ideas, concepts, or perspectives within information. This method was widely applied for oral discussions of key moral concepts and was described by Plato in the Socratic dialogues. For this reason, Socrates is often recognized as the father of Western ethics or moral philosophy.

“It’s a way of searching for philosophical truth. Typically, it involves two interlocutors, with one leading the discussion and the other agreeing or disagreeing with certain hypotheses presented for acceptance or rejection. This method is credited to Socrates, who began engaging in such debates with his fellow Athenians after a visit to the Oracle of Delphi. The practice involves asking a series of questions centered around a main topic or idea and then answering any subsequent questions that arise. This method is usually used to defend one viewpoint against another position. The best way to prove the correctness of a “point of view” is to make the opponent contradict themselves and, in some way, accept the “point of view” in question. The term Socratic questioning is used to describe this type of interrogation, where one question is answered as if it had been a rhetorical question. For example: “Can I eat mushrooms?” The answer might be another question, as if the first were rhetorical: “Aren’t mushrooms edible?” This forces the questioner to ask another question that sheds more light on the subject.” Wikipedia.

How I wish I had known this before starting law school in the U.S. I remember when I had my meeting with my academic advisor to decide which classes to take in the first semester. I was working full-time as a paralegal at a prestigious law firm with national reach, and she told me, “You should consider quitting your job because you won’t have time to study; you need at least three hours of preparation for each class.” I thought to myself, “That’s absurd! Of course not; I already studied law and didn’t need three hours of preparation per subject. I worked full-time and was also the mother of a newborn baby.” -Ignorance is bliss! Ha!

So, the hallmark of law school training in the U.S. is the use of the Socratic method, where students are called on directly by name and last name to answer questions about jurisprudence, doctrines, and legal concepts.

The Reality of 1L: More Challenging Than I Expected

Imagine being called on by name in a class of 100 students to answer detailed questions about a court ruling from 50 years ago—and all this in a language that isn’t your own. Terrifying. The first time I was called on, I got physically ill—I had a fever, headache, stomach ache, and dizziness all at once. I survived my “cold call” successfully, but it was a truly unpleasant experience.

So, my academic advisor was right—you need at least three hours to prepare for each class. (In my case, I needed a bit more.) Each class has assigned readings that are mandatory if you want to survive the questioning and maintain your dignity. For me, these readings were 100-150 pages per class, all in English, of course. I not only had to read them but also ensure I understood them fully to be able to answer the professor’s questions in the Socratic debate. Participation doesn’t carry much weight in your final grade, but if you do poorly, the professor will definitely remember it at the end of the course, which could hurt your final grade.

Facing the Final Exams

Another difference is that in U.S. law schools, there usually aren’t midterm exams or lots of assignments to help build your final grade. No, in 99.9% of my classes, your grade on the final exam is your final grade. This exam covers the entire semester’s content, and it’s unlike any other exam you’ve ever taken in your life.

In U.S. law school, they teach you a new way of writing with a specific structure aimed at persuading judges if you’re a litigator, informing clients ethically and objectively, and communicating effectively with opposing counsel. The most commonly used format for answering exam questions is IRAC (Issue-Rule-Analysis-Conclusion), though I also love CREAC. The exam consists of a series of hypothetical cases with numerous legal issues that you must resolve, answering in the IRAC format. Sometimes you’ll respond as if you’re a litigator, a law clerk, a judge, or a judicial assistant, depending on “the call of the question.”

Each hypothetical case has a set of facts you must analyze thoroughly. Each case is one or two pages long, and usually, each exam has at least three hypothetical cases. For my U.S. Constitutional Law exam, I remember writing over 10 IRAC essays in six hours. Yes, six hours—and usually, that’s not enough time.

Strategies That Helped Me Survive

So how did I survive?

First, I unlearned everything I had learned about legal reasoning in my country to make room in my mind for all this new information without resistance.

Then, I learned to stop being a perfectionist and understood that it doesn’t have to be perfect; it just has to be done. I learned that my accent didn’t matter when speaking and that I didn’t need to pronounce every word perfectly to make a successful contribution to the Socratic debate in each class. This freed me from fear, and I began to see it as fun.

I opened my mind to new study systems, researched how Americans study, and specifically how to study in law school since it’s so different from everything else. I started applying what I learned to be more effective in my preparation for each class. Preparation is key to succeeding in law school.

I researched and studied the methods for taking a final exam in law school to manage my time effectively, learn what to do and what not to do, and, of course, took practice exams. Practice makes perfect!

And I couldn’t forget to build an amazing group of friends to study with, support each other in tough times, cry and laugh together, and be there for one another during crises (which are very common in law school, ha!). Without them, everything would have been even harder.

Believing in Yourself: The Key to Success

Believing in myself was crucial. Believing that I’m capable and that it doesn’t matter that I’m learning in another language—my brain is already trained to be a lawyer, and that ability comes through when I need it, even if it’s not conscious.

My passion for justice, law, and order is so strong that it transcends all language, culture, and teaching system barriers. I’m studying law for the second time in this same lifetime. When I finish, I’ll be trained in the two largest legal systems on earth: “civil law” or Roman law, and “common law” or Anglo-Saxon law.

If you’re a foreign lawyer considering studying law in this country, do it. It will be the most transformative and rewarding experience you can have—believe in yourself, and you will succeed.

Lissie Albornoz

Leave a comment