Last Friday, I had the privilege of participating in the Clinics Kick-off event as part of my enrollment in the Human Rights at the University of Miami https://www.law.miami.edu/academics/experiential-learning/clinics/human-rights/.

It was an amazing opportunity to connect with fellow students from all the Miami Law Clinics and immerse myself in Miami’s rich and diverse history.

Personal Background: Embracing a Mixed Heritage

I should start by saying that as a Latina from Venezuela, where our races mixed during colonization, the majority of the population is of mixed heritage. About two-thirds are mestizo or mulatto-mestizo, with European, African, and indigenous ancestry.

I did a DNA test some years ago, and my genes are 52% European, 26% African, and 22% indigenous. Most Venezuelans are similarly mixed, so I grew up in a country where racial discrimination didn’t make sense because most of us carry all races in our DNA. My grandmother’s DNA test showed a similar mix, even with an additional 1% Jewish ancestry.

Understanding Racism: A New Perspective

Racism in America was initially hard for me to grasp. However, through my studies in the American academic system, I’ve gained a much deeper understanding of it from a different perspective. My recent experience on Friday further deepened my comprehension of the complex issues surrounding racism in both the past and present in America.

Historic Lyric Theater: A Cultural Landmark in Overtown

We gathered at the Historic Lyric Theater in Overtown, https://www.bahlt.org/ a venue with deep cultural and historical significance. Opened in 1913, the Lyric Theater quickly became a major entertainment center for the Black community in Miami. Built by Geder Walker, a Black entrepreneur from Georgia, the theater was described in 1915 as “possibly the most beautiful and costly playhouse owned by Colored people in all the Southland.” It served as a symbol of Black economic influence, a social gathering place free from discrimination, and a source of pride and culture within Overtown.

Miami’s Incorporation: The Essential Role of the Black Community

When we arrived, we learned that Miami officially became a city on July 28, 1896, with just over 300 residents. Some could credit the city’s incorporation to Julia Tuttle, a local landowner who persuaded railroad tycoon Henry Flagler to extend his railway to the area. However, as Dorothy Fields, founder of The Black Archives, noted in the Miami Herald, “We made Miami, … Those first 50 years, without the Black laborers, we would not have had Miami moving forward and certainly not what we have now. Not enough credit is given to the laborers.”

The Miami Herald article continues saying “Before the high rises, before the blockbuster films, before the art scene, Miami was just a sprawling plot of land that needed to be incorporated. In 1896, Florida State law required a minimum of 300 registered voters for a city’s incorporation. Miami had more than enough to fulfill the requirement — but not all were white men. Many, in fact, were Black workers employed by Henry Flagler to help clear the land for the Royal Palm Hotel.

Toiling in the fields, however, was far from some 162 Black men’s minds on July 28, 1896. Rather than report to work, they had received strict instructions to attend an incorporation meeting in the then-Miami business district. Their presence proved crucial: those 162 constituted 44 percent of the voters who established Miami. An African American by the name of A.C. Lightburn was also said to have given the most rousing speech in support of incorporation. From the very beginning, Black people played a key role in Miami’s history. Without those 162 men, Miami’s reputation as an international paradise might never have taken flight.”

Lyric Theater’s Legacy: From Entertainment Hub to Cultural Beacon

The Lyric Theater was at the heart of the “Little Broadway” district, bustling with hotels, restaurants, and nightclubs frequented by both Black and white tourists and residents. For nearly fifty years, it operated as a movie and vaudeville theater, hosting luminaries like Mary McLeod Bethune and Ethel Waters. Despite closing in the 1960s as Overtown began to deteriorate, the theater was revived by The Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida, Inc. It reopened in 2000 after extensive restoration and remains a beacon of Black cultural heritage today.

Black Archives Historic Lyric Theater: Preserving Black Heritage

Now known as the Black Archives Historic Lyric Theater, the Lyric Theater continues to serve as a cultural and historical hub in Miami. It is a part of the Historic Overtown Folklife Village and plays a key role in preserving and promoting the history and culture of Black South Florida from 1896 to the present. The complex offers various programs and exhibitions, focusing on the contributions and experiences of the African Diaspora.

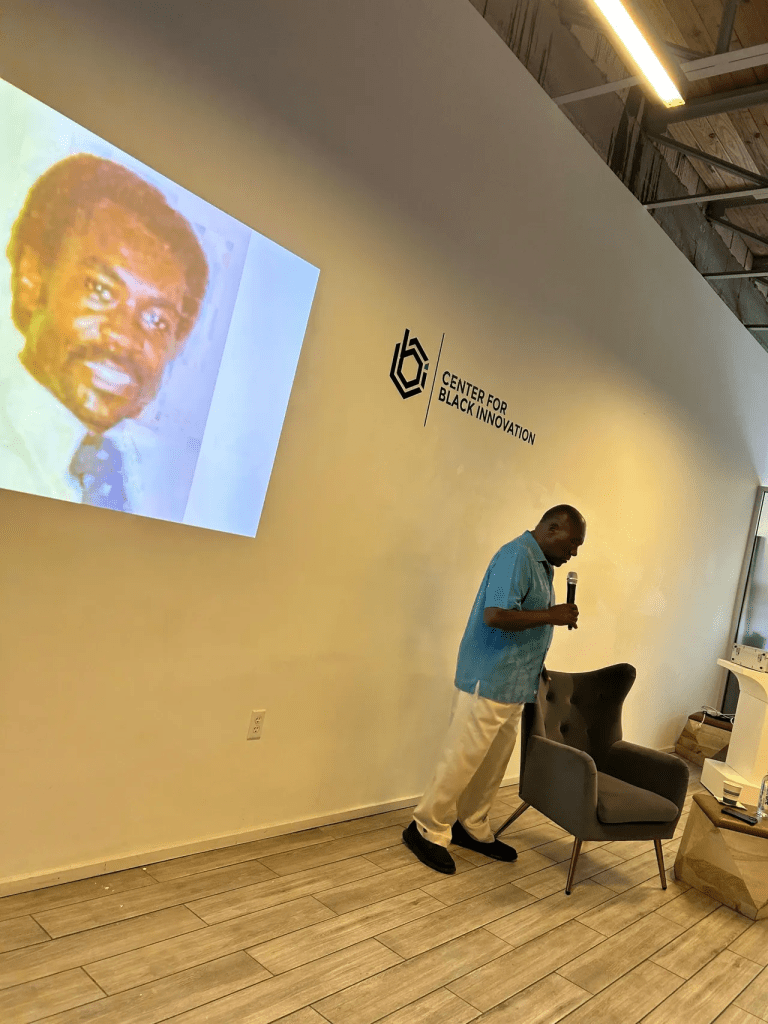

Center for Black Innovation: Fostering Community Growth

Due to the rain, we couldn’t proceed with the planned tour of the Historic Sites of Overtown, but instead, we visited the Center for Black Innovation https://www.cfbi.org/. This visit was an eye-opening experience, as the Center is dedicated to fostering innovation, economic and social mobility, business development, education, and family and community support within the Black community.

Teach the Truth Community Garden: Cultivating Knowledge and Nourishment

At the Center for Black Innovation, we were welcomed with the view of The Teach the Truth Community Garden. The Teach the Truth Community Garden is being built by Dr. Marvin Dunn and the Miami Center for Racial Justice in the Historic Overtown neighborhood. The fresh vegetables and harvest will be delivered to residents in need. There will also be a book distribution of books that exemplify Black history.

Dr. Marvin Dunn: Championing Racial Justice and History

Then we were addressed by Dr. Marvin Dunn in person.

Dr. Dunn, a former naval officer, is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychology at Florida International University, where he retired as department chair in 2006. He has written extensively on race and ethnic relations, with articles in major newspapers like The New York Times and the Miami Herald. Dunn is the author of several books, including The History of Florida: Through Black Eyes and Black Miami in the Twentieth Century. He has also produced documentaries on significant historical events related to Black history in Florida. Currently, Dunn resides in Miami, Florida. https://dunnhistory.com/

Miami Center for Racial Justice: A Community Beacon

After George Floyd’s tragic death, Marvin Dunn and other advocates founded the Miami Center for Racial Justice. Dunn describes the center as a “beacon” for the community, aiming to create a safe space for honest dialogue about racial issues. The center promotes unity and encourages the candid examination and preservation of Florida’s history of racial terror, ensuring these stories are remembered and discussed to foster understanding and prevent such injustices from recurring. To learn more visit https://miamicenterforracialjustice.org/

Florida’s Racial History: Beyond the “Sunshine State”

As it says on Dr. Dunn’s website, through his eyes, I learned that Florida wasn’t always the “Sunshine State.” This was an invention in the 1950s to attract tourists. Before that, Florida, like the southern states, was racist, just like the others, and in some ways worse. A Black person in Florida stood a greater chance of being lynched than a Black person in Mississippi or Alabama. But almost all of Florida’s painful racial past has been whitewashed, marginalized, or buried intentionally.

Dr. Dunn’s Lecture: Exploring “Black Miami in the Twentieth Century”

During his insightful lecture, Dr. Marvin Dunn discussed his book Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, which chronicles the journey of Black history in South Florida. The book covers key events, from the early migration of Black communities to Miami, through the Civil Rights Movement, and into recent times with immigration from Latin America and the Caribbean. Dunn explores the challenges faced, such as segregation, police brutality, and economic disenfranchisement, as well as the resilience and significant contributions of the Black community in shaping Miami’s cultural and economic landscape. A documentary based on the book, The Black Miami, featuring Dr. Dunn, is available on Amazon Prime.

In addition to recounting historical events, the book includes personal stories and photographs, making it a rich and detailed chronicle of Black life in Miami.

Key Themes:

- Segregation and Civil Rights: The book details the systemic segregation in Miami and the Civil Rights struggles that sought to dismantle it.

- Urban Renewal and Displacement: It covers the impact of urban renewal projects that led to the destruction of Overtown and other Black neighborhoods, displacing thousands of residents.

- Cultural Contributions: The book highlights the significant cultural contributions of the Black community, particularly in areas such as music, religion, and business.

- Political and Social Activism: Dr. Dunn discusses the political and social activism that has been a constant force in Miami’s Black community, from the early 20th century to the present day.

Overall, “Black Miami in the Twentieth Century” is an essential read for anyone interested in the history of Miami and the experiences of African Americans in this vibrant city.

The Arthur McDuffie Case: A Pivotal Moment in Miami’s History

Near the end of his lecture, he spoke about the Arthur McDuffie case. I learned that it is one of the most significant and controversial cases in Miami’s history, particularly in the context of race relations and police brutality.

The case centers around the death of Arthur McDuffie, a Black insurance salesman and former Marine, who died as a result of injuries sustained during a brutal beating by Miami-Dade police officers on December 17, 1979. McDuffie was initially stopped for allegedly running a red light while riding his motorcycle. The situation quickly escalated, leading to a high-speed chase, and ultimately, McDuffie being severely beaten by several police officers after he was apprehended.

After being stopped, McDuffie was reportedly beaten with flashlights and nightsticks by multiple officers, causing severe injuries, including a fractured skull. The officers attempted to cover up the incident by staging the scene to make it appear as if McDuffie had crashed his motorcycle.

McDuffie died in the hospital on December 21, 1979, due to the injuries inflicted by the officers.

Four officers were charged in connection with McDuffie’s death. The trial, which was moved to Tampa due to concerns about a fair trial in Miami, resulted in all the officers being acquitted on May 17, 1980, by an all-white jury.

The acquittal sparked widespread outrage and led to one of the worst race riots in U.S. history, known as the 1980 Miami Riots. The riots resulted in at least 18 deaths, hundreds of injuries, and extensive property damage, particularly in the Liberty City neighborhood.

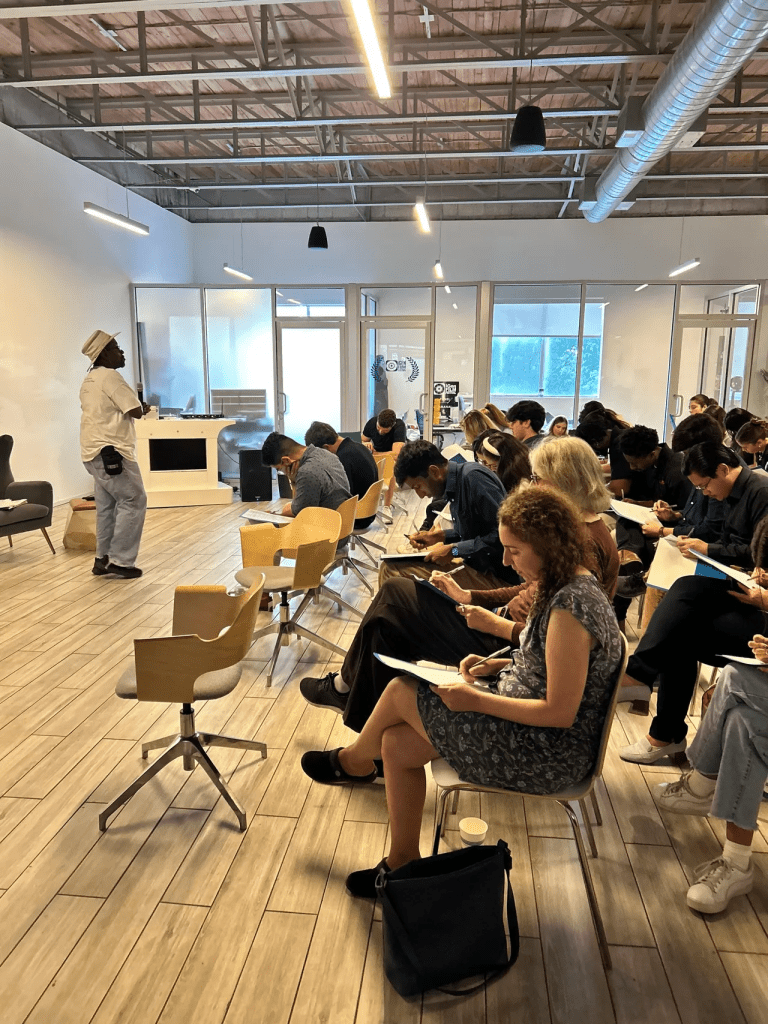

Understanding Literacy Tests: Tools of Voter Suppression

Then we learned about the “Literacy Test,” which was one of several discriminatory practices used in the southern United States, including Louisiana, to disenfranchise Black voters during the Jim Crow era.

After the Reconstruction era, southern states implemented various laws and practices to suppress the African American vote and maintain white supremacy. One of these methods was the literacy test, ostensibly designed to ensure that voters had a certain level of education. However, in practice, these tests were used selectively and unfairly against Black voters.

The Test in Louisiana:

In Louisiana, like in many other southern states, prospective voters were required to pass a literacy test to prove they had at least a fifth-grade education before they could register to vote. These tests were often exceedingly difficult, confusing, and designed to be nearly impossible to pass, especially for Black people.

- Administration: The tests were administered by local voting officials, who had complete discretion over who had to take the test, how it was administered, and how it was graded. This meant that white voters were often either exempted from taking the test or given much easier versions, while Black voters were given the most difficult and confusing versions.

- Purpose: The primary goal was to prevent Black people from voting. Even if a Black person had a fifth-grade education or more, the way the test was structured and administered made it nearly impossible to pass.

The End of Literacy Tests:

The use of literacy tests, along with other forms of voter suppression, was challenged and eventually outlawed by the federal government.

The literacy tests and other similar practices left a long-lasting impact on voter participation and civil rights in the United States. They are a stark reminder of the lengths to which some individuals and governments went to deny African Americans their basic rights, and they underscore the ongoing struggles for racial equality and voting rights in the country.

Experiencing the Literacy Test: A Personal Reflection

As a very eye-opening activity, the test was administered to us, and then we were asked to provide feedback about how we felt answering the questions.

The questions are notoriously difficult, designed to confuse and ensure failure. One of the most infamous examples comes from Louisiana’s 1964 literacy test, often called the “Impossible Test.”

Here’s an example of some of the types of questions that were on the test:

- “Draw a line around the number or letter of this sentence.”

- “Draw a line under the last word in this line.”

- “Circle the first letter of the alphabet in this line.”

- “In the space below, draw three circles, one inside (engulfed by) the other.”

- “Cross out the longest word in this line.”

- “Draw a line under the smallest number of this line.”

These questions might seem simple at first glance, but they were designed to be confusing and were often interpreted subjectively by the person administering the test. For instance:

- If you misinterpreted the instructions in any way, you would fail.

- If you didn’t follow the exact sequence or misunderstood the question, you would fail.

- The test was usually timed, often giving only 10 minutes to complete all questions, adding pressure and increasing the likelihood of failure.

Moreover, there was no answer key, and the results were at the discretion of the test administrator, who could arbitrarily fail anyone, particularly Black applicants.

During the test, I found myself re-reading the questions multiple times to ensure I understood the instructions. Initially, I thought it was just me because English isn’t my first language, but soon realized everyone else was struggling too. We had only 10 minutes to answer nearly 30 confusing questions, and not a single person was able to finish.

Participants shared that they felt confused and frustrated, to the point where they didn’t even want to finish the test because it didn’t make sense. I felt the same way, which is exactly what the test was designed to do.

Key Historic Sites in Overtown

- Mount Zion Baptist Church Founded in 1896, this church played a significant role in civil rights activities during the 1950s and 60s. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke here.

- The Dorsey House Home of Miami’s first Black millionaire, D.A. Dorsey, this house is located at 250 Northwest Ninth Street.

- The Lyric Theatre Opened in 1917, it was the social hub of Overtown, hosting many major events.

- Longshoremen’s Union Hall Established in 1937, it was one of the first unions to admit Black members.

- The Greater Bethel AME Church Known as “Big Bethel,” it was a key site for civil rights activism.

- The Mary Elizabeth Hotel Famous for its Zebra Lounge, where Black and white musicians performed together.

- The Ward Rooming House A place where Black entertainers stayed when they were not allowed to rent rooms elsewhere.

Promising to Return: A Commitment to Overtown’s History

After the event, my clinic classmates and I took a brief walk through Overtown. The rain had stopped, but it was getting dark, so we only had a chance to see the exteriors of The Dorsey House and The Ward Rooming House. I made a promise to myself to return and take a proper tour of the historic sites.

Red Rooster Overtown: A Culinary Gem and Cultural Gathering Spot

Another reason I’m eager to return to Overtown is to visit Red Rooster Overtown, a culinary gem where Chef Marcus Samuelsson infuses his passion for food into the community. In 2022, Michelin awarded Red Rooster the Bib Gourmand for its exceptional food at a great value. My clinic classmates and I stopped in for refreshing drinks, had a chance to connect and reflect on our experiences, and enjoyed the warm atmosphere. Although I didn’t get to try the food, I’ve heard it’s fantastic, and as a foodie, I’m definitely planning a return visit for a meal.

Final Reflections: Embracing Overtown’s History and Community

Finally, after almost nine years of living in Miami, I realized I had never visited Overtown or learned about its significant history, particularly the crucial role the Black community played in the city’s incorporation. Experiencing the firsthand accounts of the suffering and humiliations endured by the Black community was intense and sobering. While these stories are difficult to hear, they are an essential part of this country’s history, and it’s vital to know them to ensure such injustices are never repeated.

Thank you, Miami Law and the Human Rights Clinic, for giving me the opportunity to live this experience.

Lissie Albornoz

Leave a comment