When I began my judicial clerkship through the ABA Business Law Section Diversity Judicial Clerkship Program, I never imagined that within just a few weeks, I’d be immersed in a real bench trial—one that tested not only my legal knowledge but my analytical instincts, procedural awareness, and long-held courtroom curiosity.

After years of studying law in the United States, working in civil litigation, it finally happened: I witnessed my first trial in the U.S.

Not a mock trial. Not a simulation. A real, multi-day bench trial in the Michigan Court of Claims, in the case of West v. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. For someone like me—who came to this country as an immigrant, went back to law school, and learned this legal system from scratch—this moment was more than just a milestone. It was a full-circle realization of everything I’ve worked toward.

Law School vs. Real Life

In law school, we spend years analyzing appellate opinions, parsing hypotheticals, and writing about what “should” have happened. We’re told how a courtroom works. We read about objections and hearsay exceptions. But nothing compares to actually watching litigators argue evidentiary issues in real time, and observing how judges manage a trial from the inside out.

This wasn’t just an academic experience—it was deeply visceral. I wasn’t reading FRE 801(d)(2)(D) in a textbook. I was watching lawyers debate whether a statement by a state agency official was admissible as an agent admission. I observed cross-examinations that tested credibility, expert testimony that faced Daubert-style scrutiny, and a judge—my judge—ruling thoughtfully on each evidentiary challenge.

Case Background: West v. Michigan Department of Natural Resources

The trial centered on claims brought by Randy West and his daughter Audrey against the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR), following a snowmobile accident that occurred on January 6, 2018, in the Jordan River Valley. While riding on Trail 4, their snowmobile exited the trail near a blind curve and plunged into the river. At the time of the accident, two Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) officers were patrolling the trail on their own snowmobiles. The plaintiffs allege that the officers’ riding pattern contributed to the crash, while the defense maintains the officers were conducting standard patrol activities and deny causing the incident. The legal issue centers on whether the DNR officer’ conduct constituted gross negligence that was the proximate cause of the injuries sustained, a threshold that must be met to overcome the defense of governmental immunity under Michigan law.

But more than the legal intricacies, it was the trial dynamics, attorney strategies, and witness performance that left a lasting impression on me.

From the Front Row: Lessons I’ll Carry Forward

This went beyond anything I’d learned in the classroom—it was transformational. Here are my key takeaways:

- Preparing your witnesses is everything. A well-prepared witness is more persuasive and less susceptible to impeachment. I saw how weak preparation could undermine testimony—and how strong prep could fortify it.

- Trial prep is not just about law—it’s logistics. Having worked as a civil litigation paralegal, I already knew the importance of behind-the-scenes work. But witnessing it firsthand drove it home:

- A clearly marked, accurate exhibit list is critical.

- Demonstrative aids must be trial-ready.

- Your binder should function like a well-oiled machine.

- Strategic objections matter. Timing, tone, and legal basis aren’t just formalities—they’re tools of advocacy.

- Direct and cross aren’t just routines—they’re storytelling. Great attorneys don’t merely ask questions; they craft a narrative.

- Judicial patience is a superpower. Judge Yates exemplified balance, clarity, and control. Watching him preside with calm authority, manage timing, and issue rulings with precision was… judicial poetry.

Cases like West serve as a compelling reminder of the complexity of state liability, the procedural rigor required in civil litigation, and the human stories behind government accountability. For law students, aspiring litigators, and those interested in public service, observing trials and analyzing their structure offers invaluable insight into the practice of law. If you’re currently studying or working in the legal field, I encourage you to attend a civil bench trial, volunteer with your local court, or get involved in judicial clerkship opportunities. There’s no substitute for learning directly from the courtroom.

A Moment of Transformation

This trial didn’t just change how I understand litigation. It transformed how I see myself—as an advocate, as a future attorney. I brought to this experience the structure and discipline I learned in Venezuela, pairing it with the sharp, precedent-driven thinking I’ve developed here in the U.S.

In the end, I walked away with something greater than trial notes. I walked away knowing: I belong here. In this courtroom. In this country. In this profession.

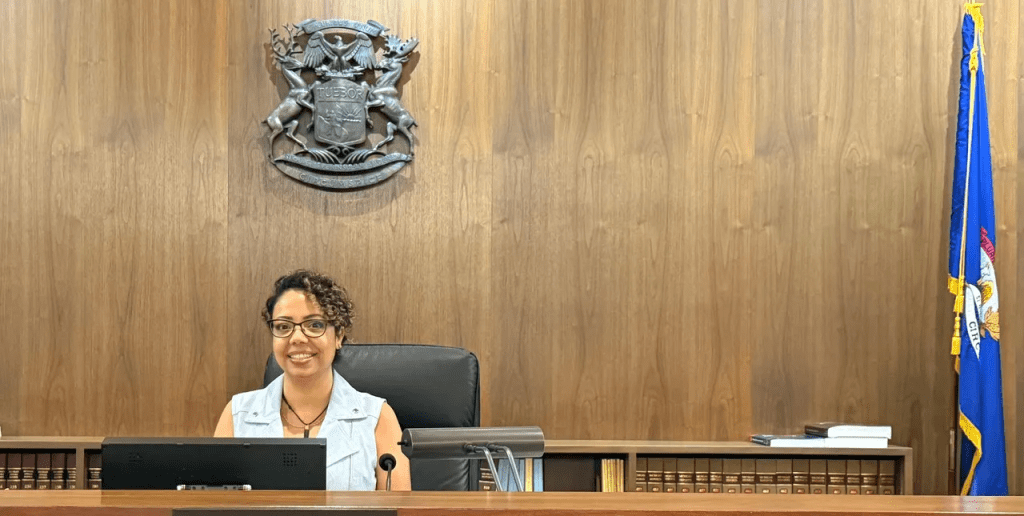

And somewhere in the gallery of observers in that courtroom sat a girl who once only dreamed of practicing law in the United States. This summer, she finally saw herself on the record.

Lissie

Leave a comment